Talking to the Beginning of the World

Today was the launch of the WeeFestival’s industry conference, bringing together 50+ delegates from across Canada and Europe.

I attended the keynote address at the Pia Bouman Studios, delivered by Dr. Ben Fletcher-Watson of Scotland. Speaking to a room full of industry professionals, Dr. Fletcher-Watson identified his interest in arriving at a dramaturgical framework for Theatre for Early Years (TEY), posing questions like: How is it made? Who makes it? When does it work? When does it fail? And, most interestingly, is failure a necessary component of the creation of TEY?

He started his presentation by discussing the “rules” or “best practices” that many Theatre for Early Years practitioners have identified, such as “it should be 30 minutes or less,” or “you should always keep the lights on.” He then stated that, more than any of these rules, what all TEY artists know is that “there are no rules.” There was a knowing chuckle from the audience. These practitioners have, I imagine, experienced the unexpected joys and frustrations that come from working with very young children. In fact, a quote on Dr. Fletcher-Watson’s excellent Tumblr page from Quebecois artist Véronique Côté sums it up for me perfectly:

“Directing theatre for babies is doing the unknown. It is engaging. It is hope in the rough. It’s trying to talk to the beginning of the world.”

There is an old theatre school parable that says to never put a dog or a baby on stage. This is because they can’t be expected understand the rules of the play, or theatre in general, and therefore they are likely to cause a disturbance or upstage the main action. I’ve seen this happen – where a baby is supposed to make a brief appearance in an actor’s arms but ends up stealing the show. This wildness, this aspect of children that makes them so unpredictable is a gift and the challenge for artists in TEY. Now recall that instead of one of these creatures being on stage, TEY artists are faced with dozens of them in the audience. How do you corral their energy? How do you allow for beautiful accidents, moments of connection, and spontaneous content while still holding the piece together?

According to research that Dr. Fletcher-Watson has collected, prototyping and workshopping is essential. It is by participating in an open-door development process that TEY artists learn what is working and what isn’t. It’s how they learn that sometimes (to quote Dr. Fletcher-Watson) “a child may vomit in a cello.” Or how they learn not to ever, EVER lie down on the floor during a performance because (to quote him again) “they will lie on top of you.” Every time.

Through trial and error, slowly and over time, TEY artists arrive at something that works. Sure, there’s always that kid who’s going to puke in a cello. But for the most part, the artists come to know the peaks and valleys of energy and attention, where kids get fidgety, where they are rapt. They begin to stockpile feedback from parents, who are just as important an audience; because if a parent is bored it’s likely their child will sense it. And, slowly but surely, artists can arrive at something that is somewhat codified. A road-map for a show that allows for shortcuts or pit stops as needed. A plan, yes, but one you’re expecting to break.

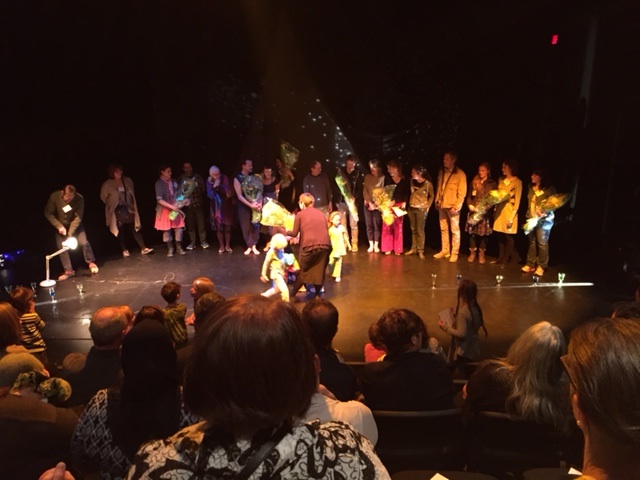

Applause for the festival artists!

This reminds me of parenting. The more I work at being a parent, and realize what a full-time job it is, the more I try to find an appropriate analogy for this career that is currently my focus. So what exactly is my job? And the job of other temporary or full-time stay-at-home-parents?

Is it like being a traffic cop? Or a maid? Chef? Playground attendant? (Maybe a pinch of each.) But I believe that parenting is more like being a farmer than any other profession. Because what you are dealing with on a daily basis is a natural phenomenon (like the weather) that sometimes, but not always, has patterns. And sometimes the patterns change. (Insert sleep-deprived parent story about teething here!)

Forgive me while I continue the lengthy analogy: For a farmer who is deciding when to till or harvest, they are relying on a set of complex cues from the weather and their natural environment. For a parent who is deciding when to put a child down for a nap, the same process of analysis applies – you can read all the almanacs you want, but at the end of the day you are using gut instinct and a tangle of natural cues from your child to make the right decision. Great TEY artists follow the same logic, which is why in many ways it’s very much like parenting. They’ve learned the rules. They’ve broken the rules. They’ve practiced. They’ve made mistakes. But at the end of the day, as they walk out on stage in front of a gaggle of toddlers, these artists are like that farmer, or that parent: licking a finger and sticking it into the wind.